Beyond Open Access: Building Justice in Scholarly Communication

Leadership requires and demands justice.

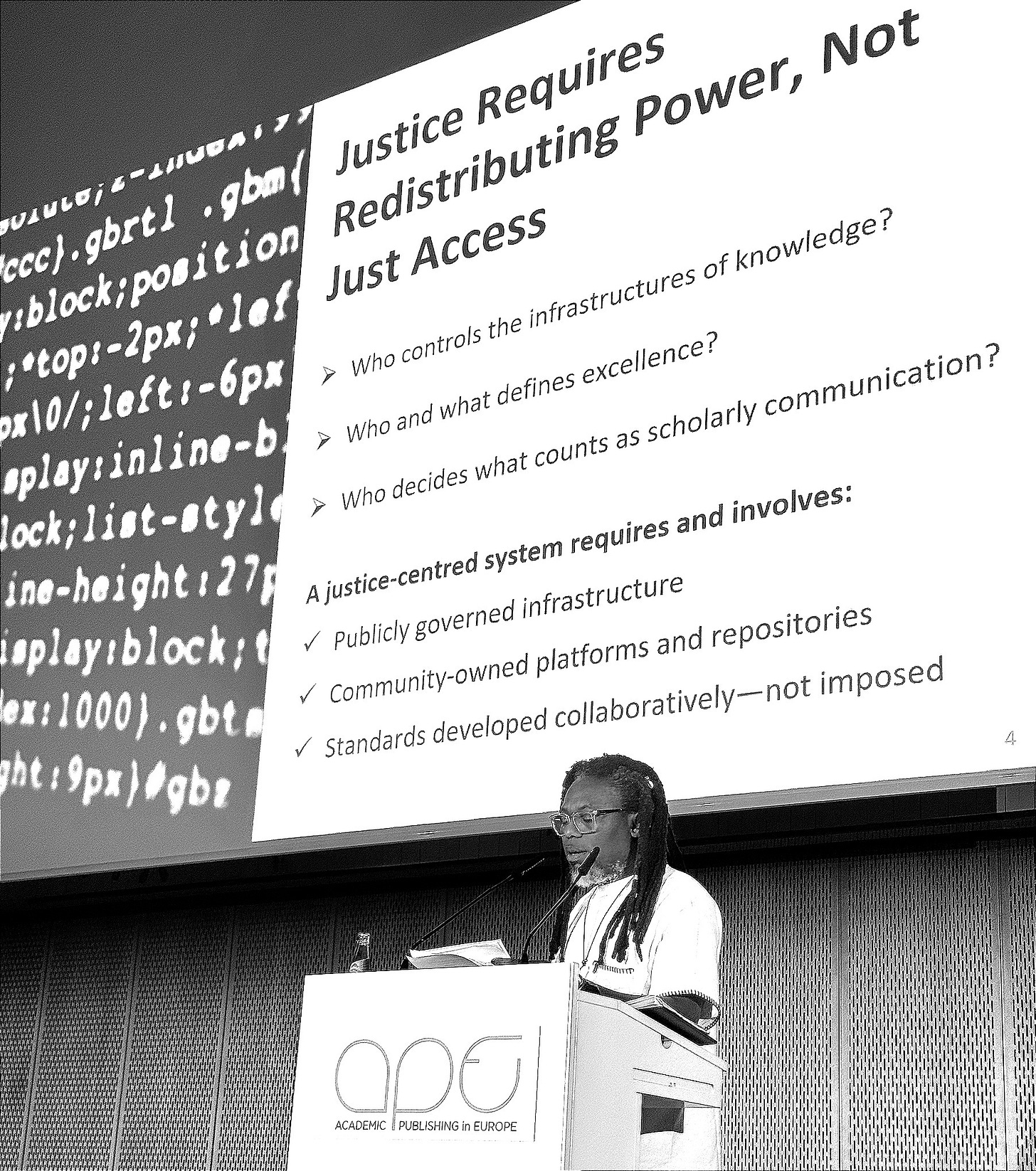

This is an abridge version of keynote I gave at the Academic Publishing in Europe conference in Berlin, Germany this week.

Good afternoon, and thank you for the invitation to speak today.

In this keynote, I will address the following key questions:

What should justice in scholarly communication actually involve

Who needs to be involved; and who is currently missing

The role and place of community in shaping a fairer system

How justice could be meaningfully measured

And critically, what are the ethical frameworks that should guide the technologies we deploy.

We often celebrate how far Open Access has come, from a radical idea to a mainstream expectation. And that progress matters. But today I want to suggest something more challenging:

Open Access is necessary, but it is not enough.

Openness is a mechanism.

Justice is a goal.

And if we want a scholarly system that is truly equitable, globally relevant, and ethically grounded, we must move beyond access toward what I call justice-centred scholarly communication.

1. The Limits of Openness Without Justice

Open Access promised a simple idea: remove paywalls, and knowledge becomes democratic. But what we have done instead is replace one barrier with another.

We removed the paywall to read, but introduced a paywall to publish.

Article Processing Charges have become proxies for prestige.

And those without institutional funding—researchers in the Global South, early-career scholars, independent researchers—are systematically excluded.

The APC waiver system is often presented as the solution. But waivers do not redistribute power. They are discretionary, inconsistent, and often humiliating. Justice framed as charity is not justice at all.

So, what we have is not an open system—it is a reorganised hierarchy.

Open Access has increased visibility, but it has not delivered equity. It has not addressed whose knowledge is valued, whose language is privileged, or whose work counts in hiring, promotion, and funding.

Openness without justice risks becoming performative.

2. Justice Requires Redistributing Power, Not Just Access

If we are serious about justice, we must ask harder questions:

Who controls the infrastructures of knowledge?

Who and what defines excellence?

Who decides what counts as scholarly communication?

Today, those decisions are concentrated in the hands of a few powerful actors; often disconnected from the communities they [claim to] serve.

Justice is not about opening the door to the same room. It is about working with those allowed into the room to participate in re-organising the room to everyone’s comfort. In fact, it can, and should go as far as redesigning the building altogether!

A justice-centred system requires and involves:

Publicly governed infrastructure

Community-owned platforms and repositories

Standards developed collaboratively—not imposed

Justice means redistributing power, not just lowering barriers.

3. Justice Means Recognising All Forms of Knowledge

Another deep injustice lies in what we recognise as legitimate knowledge.

The global scholarly record overwhelmingly reflects:

English-language work

Euro-American academic traditions

Text-based, peer-reviewed articles

and many more factors

But knowledge also lives in Indigenous epistemologies, community-led research, practice-based work, local languages, data, code, methods, and lived experience.

These forms of knowledge are not marginal.

They are marginalised!

A justice-centred future does not merely tolerate diversity; it actively values epistemic pluralism.

4. Justice Requires Rethinking Incentives

At the heart of inequity is how we evaluate research and researchers.

As long as prestige is tied to a narrow set of journals, no amount of Open Access will produce justice. And we should ask ourselves honestly—is that system even open?

We need a shift:

From impact factors to impact on communities

From quantity to quality and integrity

From competition to contribution

Funders and institutions hold enormous power here. The incentives you - Funders - set shape researcher behaviour.

A justice-centred system rewards collaboration, openness, data sharing, public engagement, and contributions to, and from shared infrastructure; not just citation counts.

On the matter of infrastructure, I want to discuss with you the…

5. Ethics and Governance of Technology

We also cannot ignore technology, especially Artificial Intelligence.

AI is now embedded in peer review, discovery, metadata, and evaluation. But AI systems are not neutral. They inherit the biases of the data they are trained on and the assumptions of those who design them.

If the scholarly record is already skewed, AI will amplify those inequities—at scale.

Justice today requires:

Transparency in algorithms

Representative and multilingual training data

Community oversight

Strong ethical governance

Technology must serve justice, not undermine it.

6. Justice Requires Collective Action

No single actor can build justice alone.

Not publishers

Not libraries

Not funders

Not policymakers

Not researchers

But together, we hold every lever.

Justice emerges when:

Publishers move away from exclusionary business models

Libraries invest in community-owned infrastructure

Funders align incentives with equity

Policymakers legislate for public governance of knowledge

Researchers produce, share, and apply knowledge in ways that advance equity, amplify marginalized voices, and participate in shaping a just scholarly output

And at every stage, we must ask:

Whose voice is missing? Who is not in the room?

Representation without accountability is not justice.

7. From Inclusion to Involvement

This brings me to a critical distinction: inclusion versus involvement.

Inclusion has become a tick-box exercise.

Justice requires involvement - not just inclusion.

Involvement means communities are:

Engaged from the start,

Actively listened to,

Empowered to shape decisions, not just respond to them.

Genuine engagement is iterative, relational, and sustained. Without it, we repeat the same mistakes, waste resources, and reinforce exclusion.

Excluding communities is not only unjust—it is inefficient.

For the avoidance of doubts, community in this instance is the stakeholders, from early career researchers to editors, funders, policy makers, librarians, publishers and other institutions within the ecosystem.

Community engagement therefore is the act of deliberately involving target audiences and stakeholders in a meaningful way to enhance equity, and inclusion. It demands for open and effective listening, acting on what was said, and treating each other as partners, not subjects.

Only these steps results in involvement, a state of enhanced inclusion, to achieve a just outcome for all.

8. A Justice-Centred Funding Structure

We know that the current funding structure is not serving scholarly communication well; in many ways, it sustains the very problems we seek to address. Beyond paywall-to-publish, opaque and poorly designed funding formulas continue to shape inequitable outcomes.

I fully acknowledge the complexity of this ecosystem. Yet, if a just Open Access is grounded in collective participation, then funding should reflect the same principle. Imagine a shared, community-governed fund, akin to a sovereign fund, regularly reviewed to ensure fair, diverse, and inclusive distribution for the benefit of all.

Such a model would redirect resources away from paywalls and prestige, toward open infrastructures that serve the public good. This would better support underfunded researchers, institutions, and regions, while valuing collaboration, transparency, and real-world impact over competition, profit, and narrow metrics, strengthening scholarly communication for everyone.

9. A Justice-Centred Gender representation

As a man [at a very basic categorisation], I am aware of the default privileges I inherit in a world where men are often treated as the standard. Opportunities we take for granted are navigated differently by women and gender-minority colleagues.

Although women make up the vast majority at entry levels, they remain rare in leadership, editorial boards, and funding decisions.

Why do so many leave [the career]?

Why do so few reach the top [in the industry]?

Justice goes beyond openness. It is highly proven that diversity improves outcome. Gender should be a strength, not a barrier, shaping who decides what research is funded, published, and indexed. This is not tokenism! But a fairness that will bring added value in knowledge.

To achieve it, we must review hiring and promotion practices, consider maternity and caregiving support, and ask why talented individuals step away. This includes non-binary and gender-nonconforming colleagues too. Every individual we exclude is a perspective we lose.

10. A Justice-Centred Scholarly Future

So, what does success look like?

Well, it would be a system where;

Cost is never a barrier

Infrastructure is community-governed

Knowledge from Nairobi, Dhaka, Bogotá, or Auckland contributes and shapes global scholarly conversations, frameworks, principles, outcomes, and processes on equal footing

Research assessment values community impact, and cultural knowledge

Technology – and AI in particular – amplifies marginalised voices

This is not utopian!

It is achievable — if we choose justice as the goal, not just openness.

So the question I pose to us is: are we ready to explore what is possible when justice - not just openness - guides our choices?

Closing

Open Access was a crucial first step, but it cannot be the final destination.

The future of scholarly communication must be justice-centred: structural, epistemic, ethical, and global.

We have the tools.

We have the resources.

And we have the responsibility.

But are we lacking in the action?!

Justice begins with the choices we make, in how we design, fund, evaluate, govern, and involve the communities our knowledge systems are meant to serve.

To answer the five key areas, I set out to explore in this keynote, let me summarise this way

What should justice in scholarly communication actually involve

Redistributing power through

Democratisation of knowledge and its infrastructures

Diversified definition of excellence though collaborative agreements

Equitable decision in what counts as, and in scholarly outputs

Who needs to be involved; and who is currently missing

Publishers

Librarians

Funders

Policymakers

Researchers

All stakeholders

The role and place of community in shaping a fairer system

Publicly-governed infrastructure

Community-owned platforms and repositories

Standards developed collaboratively, not imposed

How justice could be meaningfully measured

Impact on communities not impact factors

Quality and integrity not just quantity

Diverse contributions not competition

And critically, what are the ethical frameworks that should guide the technologies we deploy.

Transparency

Representation

Community oversight

Enhanced, iterative and oft-reviewed governance policy

Thank you.